|

This isn't really a step-by-step guide to making a

webcomic or anything... this is just the process I use when making a strip, in

general. I also mention the things that I think about when I'm developing one,

to give a little insight about the mechanics of the strip and my art process in

general. |

|

The Sketch |

|

This

was actually just a "general" sketch I had done more than a month ago. I

have several of these. They're useful when the location isn't as important

as the text or characters. Astute readers will notice

that the sketch I used for the "In The Works" image didn't actually show

up in the final strip. There are a few reasons for that, but mainly, it's

my strip, and I changed my mind about what I wanted to do with it. :)

You'll live. Once I have thought out the dialogue and

layout of the strip, I needed to draw it. Actually, dialogue is a huge

part of the layout, and probably mostly overlooked by amateur comic

artists. I make a special effort (most times) to make sure that I A: have

enough room for the dialogue (word bubbles), and B: the layout of the

panels and placement of the characters are conducive to readability. I've

messed up a few times, but I'm working on it. |

|

|

Formatted Sketch |

|

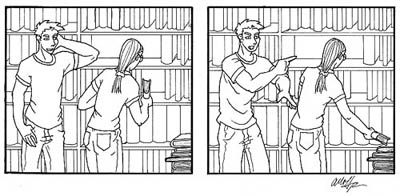

This is "actual size" on paper, though on this page it's been shrunk down

for viewing. Sometimes my format sketches are smaller than the final

drawing size (which fills most of an 8.5"x11"). In those cases, I use my

scanner as a photocopier to enlarge the sketch, in order to make a

full-size ink. Note that the scan is pretty light - I've

actually darkened it a bit. I don't usually ink right over my pencils, but

lately with R.D.T. strips, if I manage to do my pencils neatly (and not

press too hard or erase all over the place) then I'll use the same sheet

for inking.

Also note that I didn't do the books at all - the background I left as a

"suggestion," though I DID straighten the shelves out. Incidentally, I use

a T-square for straight lines (including the borders), which ensures that

the line I draw will be perpendicular to the edges of the paper.

Ms. Harper in this case was traced via lightbox from the sketch, since she

doesn't move. Why redraw something twice when you did it fine the first

time? However, her relative position changed in the sketch, to better fit

the panel's layout. The panel needs to fit Davis, Ms. Harper, as well as

the partially-shown stack of books.

The other thing I keep in mind when doing the formatted sketch is the

placement of the characters not only in the panel, but to each other.

Davis's hand is pretty much touching Ms. Harper. That's probably a mistake

on my part, I should have let his hand overlap her a little. It would have

suggested depth, instead I got sort of a "cramped" look. Ah well, c'est la

vie. Note that I have left a lot of empty space for word

balloons. This is when I also begin to think about color. More on that

later. |

|

|

Inks |

|

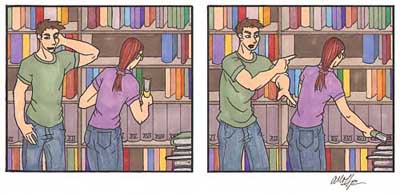

In this instance, I've inked right over my pencils, and

then erased the pencil. I can't do that with all of my strips, either

because I've gone over the pencils so much as to marr the paper, or

because the strips were sort of "all over the place." In those cases, it's

easier to use a lightbox to re-draw the inked version on a new sheet of

paper. I did use a lightbox on this piece to duplicate

the bookshelves (as well as Ms. Harper, earlier). After drawing them

neatly (with my .01 pen and t-square) in the left-hand panel, I

photocopied it with my scanner, and used a lightbox to trace the

right-hand panel from it. This way, I get the same background without

making a hundred mistakes. I use pens of different width

to suggest foreground and depth. It's hard to tell in this small version,

but the outline around Davis and Ms. Harper (and the stack of books) is

slightly thicker than the lines I used for the books/bookshelves. This

"pops" them out into the foreground. It's an old trick. Also notice the

thickest line is around the panel borders. That way it acts more as a

"frame." I already knew that I wanted to experiment with

a different coloring style with this strip. Up to this point, I had been

inking with little depth, and relying on the coloring process to put

things in the background or foreground, to render it more or less

important to the eye. With this strip (and possibly future ones) I wanted

to color it "flatly" - saving me time in the long run, hopefully, and

making the panels look less "cluttered" with color. Line width is crucial

to flat-color comics, because that is where you're going to get your

depth. Incidentally, for those who like comics and want

to read more about the mechanics and methods in them, check out Scott

McCloud's Understanding Comics. It's an excellent book and really

illustrates a lot of the theory and planning that goes into a comic. There

are quite a few "unnoticed" aspects of a comic that are essential to a

successful strip. He also has a book called Reinventing Comics that is

geared specifically toward webcomics. I haven't read it, but I have heard

that it's also quite good. |

|

|

Color, At Last! |

|

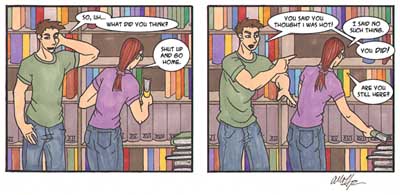

I'm a big color buff. I'm usually more interested in the

coloring techniques in an image than the actual drawing techniques. My own

style is relatively simple, so it makes it easy to color each R.D.T.

strip. A lot of webcomics out there either A: aren't colored, or B: are

colored digitally. For that reason I decided to color R.D.T. with markers,

though digital coloring would probably have been faster. (I still use

digital coloring in some cases - there was one strip which I am planning

on redoing, and there is the 4th of July image/strip. That project was too

big to take on with just markers.)

In some cases, I do fill in the backgrounds digitally. If there is a large

area of blank wall, I'll use PhotoShop's "Fill" tool rather than use up my

$3-apiece markers. I'm still working on getting the "filled" portions to

mesh well with the hand-coloring. In this case however, it's all marker.

Generally, when I do a background, I use "muted" colors. This way the

brighter colors (like the colors I use for hair and clothes) will visually

stand out, helping put them into the foreground. In this case however, I

felt free to use dozens of colors for the books. Why? The books are small.

The figures are large. Their clothes are larger areas of color than any of

the books. The "mosaic" of colored books in the back actually makes them

fairly uninteresting to the eye (without being a boring background),

whereas the bright, large color on Davis and Ms. Harper immediately draw

the eye. "Hey, we're big, look at us!" Additionally, the books are all

linear and relatively uniform. Ms. Harper and Davis's organic shapes pull

them out of the background, also. I would never have made a background

that busy if they weren't all rectangular. Note that I used some of the

same colors in both their clothes AND the books - this is a visual trick

to help "mesh" the fore and backgrounds, so they don't look like they're

just stuck onto a background. Note the second-to-bottom

row of books. They're all the same color (they're a Dangerous Thing, keep

an eye out for them in the Danger Showcase.) They're encyclopedic in

nature, so needed to match, color-wise. Rather than risk drawing attention

to them, I colored them a "middle grey." You notice them (which is good,

since they're a featured Dangerous Thing) but they don't detract from the

foreground at all. The last note about this process is

the extent to which I colored. I KNEW there would be word bubbles above

and to the right of Ms. Harper - but I colored those areas anyway. Some

people don't bother coloring what they know will get covered up, but I

don't do that. I don't like leaving things incomplete anyway, but I also

never know when I might want a "bubble-free" version, or something. It

just makes for nicer originals. |

|

|

Dialogue is King |

|

On a technical note, I add the word bubbles in Adobe's

PhotoShop. It's easier than you think. First I use the type tool to write

the words I want, in the font I want. For instance, most dialogue is done

with A.C.M.E. Secret Agent 10pt (Blambot). Davis's whining is done in

Wichita 16pt (Ray Larabie?). I move those text layers to where I want them

to be.

Then I make a new layer that is between the

background (the strip) and all the text layers. Using the oval-select

tool, I draw the bubbles. You can move them to fit correctly around the

text if you misjudged the origin point. By "correctly," I mean that the

text should fit comfortably inside the bubble, with "breathing room" all

around. Otherwise the words look cramped. Then, Edit-> Fill-> Foreground

Color (which I set to white.) Do that for all the word bubbles, then use

the freehand selection tool to add the pointers. I use an "Outer Glow" set

to 100% opacity, 600% intensity, and 2-pixel blur to do the outlines.

Borders can be used to distinguish between overlapping bubbles, also - see

the top-right trio of dialogue. (I use two layers of word bubbles for

that.) I've seen some comics who give their word bubbles

really thick outlines. I don't like that (unless it matches with the rest

of their line widths, such as Penny Arcade), because it pulls them up into

the foreground even further than the characters, or whatever the

foreground is supposed to be. I set mine at 2 pixels to match the same

width as the background lines' width. The bubbles' whiteness is enough to

pop them out. Note I've had to cover up some of my lovely

books, but that's fine. Covering chunks of non-essential background is

better than covering a character's head, or breaking way out of frame. (On

a side note, I DO break a word bubble out of frame intentionally, just to

break things up a bit, or to "connect" related frames... look for them!)

The only downside to my "don't cover the character if I don't have to"

rule is that one in twenty I'll have an awkward looking word bubble, that

doesn't seem to fit into the overall flow of the word bubbles.

Also note that the word bubbles read left-to-right, as far as the

conversation goes, as well as up to down. That's what I meant by "flow."

The reader shouldn't have to figure out what they're supposed to read

next. If I were in Japan, the whole comic would be flipped around, because

they read right-to-left. Dialogue flow in a comic is trickier than you'd

first think - I've made a few questionable word bubbles.

That's really it. I hope you found it interesting. There's a lot more that

goes into a comic than I've mentioned here, but this isn't the Complete

Theory of Comics or anything. If you want that, go get Understanding

Comics. This is just what I do. |

|